The android is unresponsive, standing frozen mid-step with one foot off the ground. I hold its metal head in my hands, tilting it this way and that as I stare into its cold red eye. It offers no resistance to my pushes and pulls, as though I was a hairdresser directing a patron’s head. Based on Stanisław Lem’s 1964 novel of the same name, The Invincible’s Firewatch-like first-person adventure is intent on exploring how machines will come to shape humanity’s future. Over the course of its ten-hour story, where you step into the Soviet-styled space boots of biologist Yasna, you will take on her desperate search for the missing crew of her research ship, The Dragonfly, lost somewhere on the rocky, sandstorm-whipped world of Regis III.

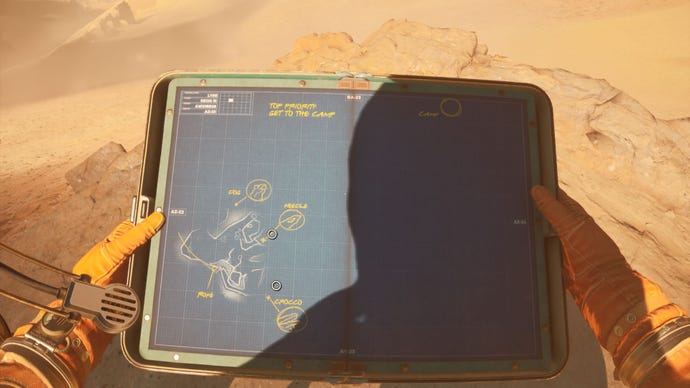

Using a logbook filled with hand-drawn maps and scrawled notes, I’ve tracked Yasna’s crew to a makeshift game to the east of where they originally landed. Instead of humans, I find the lifeless robot. I want the android to give me answers, to tell me where my crew mates are, to explain what happened on Regis III, and why I can’t remember anything before I woke up in the desert with my possessions scattered around me.

As far as I can make out from Yasna’s pre-amnesiac notes, the Dragonfly’s crew of scientists landed on the planet’s surface, visited the ocean to take samples, and headed inland to explore some strange readings taken from orbit. How she was left alone, lost her memory, and the crew’s whereabouts are a mystery that unravels as you progress through The Invincible’s first-person mystery.

Similar to Campo Santo’s Firewatch, where your explorations of the Wyoming wilderness are accompanied by observations from your character Henry, Yasna narrates much of what she sees as you clamber up and down the rocky slopes of Regis III. When you fix your radio and regain communication with your captain who orbits above in his research ship The Dragonfly, those monologues become dialogues, with the two scientists discussing the advance of machines, evolution, and what could have formed the strange metallic plantlife you discover on the planet’s surface.

It’s easy to become absorbed in The Invincible. Its mystery draws you in, doling out the occasional flashback to events on The Dragonfly before your crew went down to the surface. The vignettes give you greater context to the lives of the crew whose fate you discover one by one. The world, too, is evocative, with each vista looking like the cover of a pulp sci-fi book from the ’60s. The spaceships are smooth-sided chrome darts, the surveillance probes that aid your navigation across the barren planet’s landscape are silver balls with hover jets on the sides, and your tracker is a box with a ring of LEDs that light up when they detect a beacon.

It helps, too, that developer Starward Industries have poured so much care into Yasna’s interactions with the world, which are all viewed up close and in the first-person. Her hands and feet forever come into view as she climbs rocks, flicks switches on machines, and inspects strange objects she discovers. While the technology you encounter has taken a crew of scientists into space, it’s all activated with chunky dials, buttons, and punch cards. There’s a blunt physicality to almost everything you do.

The Invincible is at its best when you have to use this hands-on technology to learn about the world around you. When you first wake up on Regis III, you use a telescope and your logbook to identify landmarks to better navigate to your camp; when you’re near a crew member, you follow the tracker’s LED lights that blink to indicate direction and proximity to a beacon; and, you can view a probe’s recordings, not by watching back footage, but flicking through the sheets of photos they took of the action. Each cell is shown as a graphic novel-style rendering of the action. These physical interactions, all performed in your eyeline, embed you in Yasna’s body; I became attuned to her mission and enthralled by the action. In the moments when I became lost in Yasna’s head, it didn’t matter that the world was largely linear, and that you wander between dialogue triggers with only the occasional light puzzle to solve.

However, the weakness of The Invincible lives in its strengths, and it’s not unique to this game; it often breaks the spell of first-person adventure games: anytime I didn’t know where to go, what to do, or how to do it, I felt clumsy, and all of its boundaries came into focus.

| Image credit: Rock Paper Shotgun/11 bit studios

At the camp where I first discovered the placid robot with its cold red eye, I found a tent with multiple chambers. In the main compartment were items left by the missing crew, none of which I could interact with; in the second, I found even more clutter. All of it hinted at the story, but none needed to be activated to progress. In the third chamber, I found something I won’t reveal, but the game wouldn’t shift on until I found a clue to the crew’s whereabouts. I searched the room repeatedly, feeling increasingly stupid as my search continued. The note I sought was in the second chamber I had already searched, but I couldn’t interact with it until I had visited the third chamber. It left me feeling stupid, but also frustrated with the game for not anticipating I might visit one chamber before another. And at other points, it can be easy to miss the entrance to tunnels or exits from areas, leaving you walking in circles looking for the way forwards. It doesn’t help that Yasna can only sprint thirty paces or so before her visor fogs up from the exertion and she needs to take a break.

Frustrations can also seep into how you might handle objects. From the moment you start the game, it trains you to interact with things using a left click of the mouse, but any time it deviates from this template it can leave you feeling awkward as you work out what to do. This is worse when most interactions are more basic than you anticipate. When I first entered a moon buggy, I looked at the dashboard with no clear idea of how to turn it on (you press D). You can left-click on the ignition, but Yasna doesn’t turn the key, so spent a few seconds holding the starter without knowing how to make the Ph.D.-wielding space scientist turn it. It feels obvious the moment you work it out, and there are unobtrusive prompts that appear in the corner of the screen at times. But, for a game that holds your hand tight almost all the way through from start to finish, it is disorientating any time the grip slackens.

A less forgivable clumsiness lies in The Invincible’s story. I won’t spoil anything; I will only say that when Yasna has the opportunity to leave Regis III (around midway through the game), I was not convinced by her reasons to stay. And, for a game where you spend your entire time in her head, it felt uncomfortable to be so at odds with her motivations and to not care about the aspects of the mystery she still wanted to solve.

That same discomfort arose in the last hour of the game, where Yasna delivered long speeches on the nature of the Regis III and its history that felt unearned, containing theories and speculations that were great leaps from what I had discovered. I had been in her head every step of the way, so to hear my character spout knowledge I didn’t have access to was discordant.

Oddly, The Invincible is at its best when you are like its simple automatons, following instructions to complete a clear objective. However, as soon as your instructions become unclear, you can find yourself walking in loops or frozen part-way through an action, unsure of what to do. The game is a great example of how engaging first-person narratives can be, but also how any missteps or unearned moments can eject you from the head of the narrator, leaving you cold and confused.

This review was based on a review build of the game provided by developers 11 bit studios.

Credit : Source Post